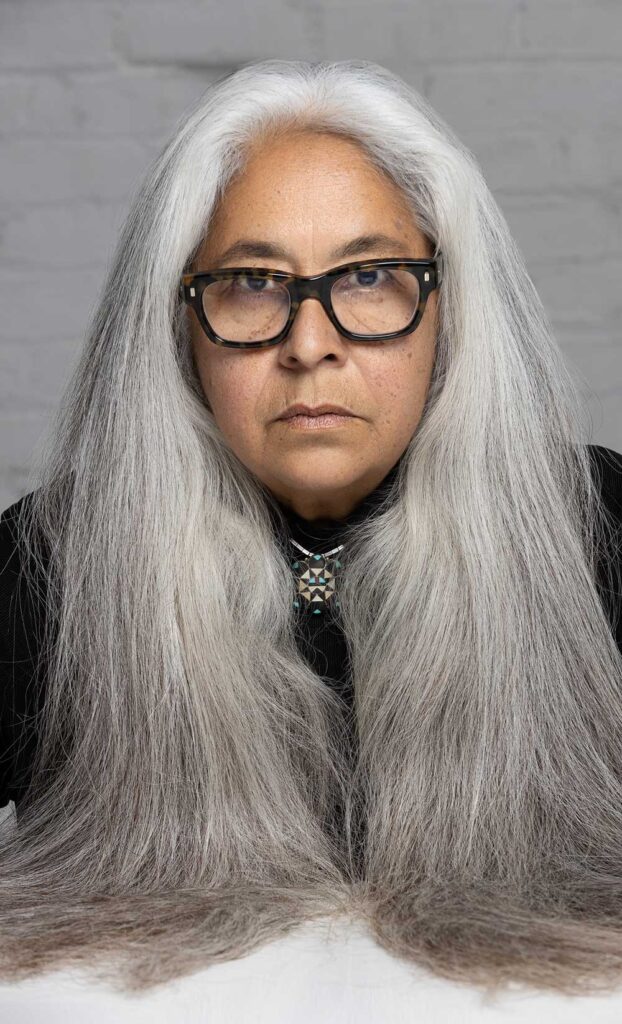

Laurie Steelink. Photo by Argel Rojo, Courtesy of Los Angeles Performance Practice

Laurie Steelink. Photo by Argel Rojo, Courtesy of Los Angeles Performance Practice

Meet Laurie Steelink, a multidisciplinary artist and a Native Scholar in Residence at Pitzer College’s Community Engagement Center (CEC) this semester. Steelink identifies as Akimel O’otham and is a member of the Gila River Indian Community.

Born in Phoenix, Arizona, she was adopted out of her Akimel O’otham Nation and raised by a white family in Tucson. She has a BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and an MFA from Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University. She recently received the California Arts Council’s Individual Artist Fellowship.

Get to know Steelink in this Q & A:

What should people know about you?

My parents were active in the Civil Rights Movement. I grew up with a good foundation in education and political consciousness. But I didn’t grow up with my culture and traditions. I found my birth mother in my early 40s. It’s been an ongoing discovery about where I come from, my ancestors, and my people’s culture.

I’ve learned about Native American art since I was a child. I was immersed in European art history in school. Native American art was only touched on in art history and was considered primitive. Now, there are more contemporary Native American artists who incorporate aspects of their traditions, culture, and history.

I was involved in reviving the four-day spiritual and cultural ceremony called the Many Winters Gathering of Elders in San Pedro. I’m on the organizing committee, and we’ve held four Gatherings since 2017. That’s greatly informed me as a human being and as an artist. My life is my art. I bridge the gap between what most people understand as art and life.

What are you doing as a Native Scholar in Residence?

When I was appointed as a scholar, I thought: “I don’t have a PhD.” However, I have an MFA, and I’ve gone 63 times around the sun. This is a reciprocal position. I have experience and knowledge, and the students do as well. I’m taking students on field trips to see exhibitions.

The Native Indigenous Student Union and I are developing ideas for an on-campus mural. I’m offering sessions for students to sketch out ideas while discussing the overall message. I recently invited Mer Young to share her work as a visiting artist for inspiration and connectivity.

I’m listening to the students’ experiences living and being educated in a predominantly white institution. I’m offering ideas, suggestions, and programming for how to implement change given my skills as an artist and cultural practitioner. There’s a need for more Native and Indigenous presence on all levels of the institution (Pitzer, the 5Cs). And a more formal recognition and understanding that all of the land occupied by the 5Cs is Native and Indigenous unceded territory, as is all of California. It’s important that we are aware of what has taken place, what trauma exists, and how to heal from it.

Laurie Steelink, GATHERING POWER III (Indian market booth), 2024. Mixed media installation.

Laurie Steelink, GATHERING POWER III (Indian market booth), 2024. Mixed media installation.

How does your Native heritage inform your work?

When this position came up, I was developing GATHERING POWER III (Indian market booth), 2024, a living multimedia installation. I’ve participated in Indian Markets as a contemporary Native artist. My work isn’t seen as traditional, but it is inspired by the traditions of my People.

Laurie Steelink, Spirit Painting No. 1, 2022. Shredded acrylic painting on canvas, metal bells, paper, glue, synthetic pom-poms, and metal stand.

Laurie Steelink, Spirit Painting No. 1, 2022. Shredded acrylic painting on canvas, metal bells, paper, glue, synthetic pom-poms, and metal stand.

For a while, I did abstract paintings that were colorful and organic. When I went to the Santa Fe Indian Market, I started making pieces cut from older paintings, as if I took a painting and broke it apart like a pot. Then the shards from the painting became their own entities. They had an energy and power.

A couple of years ago my market booth was included in an exhibition at the Orange County Museum of Art. The museum is on the unceded territory of the Acjachemen Nation. In conjunction with my booth, I organized an event with the Acjachemen spiritual leader, who shared their creation story and sang traditional songs with their singing group. The experience with the booth and the presence of the First Peoples of the land was extraordinary.

I like to build bridges. I think about where we are, who we need to thank, and whose permission we need. Often, we’re working backward, but it’s essential. When I do exhibitions, I’m also doing a residency or outreach. I don’t want my work just to hang on the wall. I want engagement.

Education has been used as a tool for settler colonialism and assimilation. What does using anti-colonial practices in higher education look like?

Bringing in Native Scholars in Residence. If I had that when I was an undergrad, it would have changed my life. Later I found out so much about San Francisco and contemporary Native American art in the 60s. I didn’t know that when I was going to school there.

By having the Native & Indigenous Initiatives and Native Scholars in Residence, we have an organized voice. We want to develop relationships with the administration so people who come, especially Native and Indigenous students, feel supported. Pitzer does not have a Native American Studies program; that should be a department.

Any Native artists that you would recommend?

New Red Order. They’re incredible. Other contemporary artists are River Garza, Ishi Glinsky, Natalie Ball, Mercedes Dorame, Jeffrey A. Gibson, and Demian Dinéyazhi’.

Learn more about Laurie Steelink.