Office of the President

Our Mission

The Office of the President represents the College with professionalism and dedication. We strive to be courteous, efficient, and effective problem-solvers, fostering communication across all groups and advancing the College’s mission and goals.

Explore Our Office

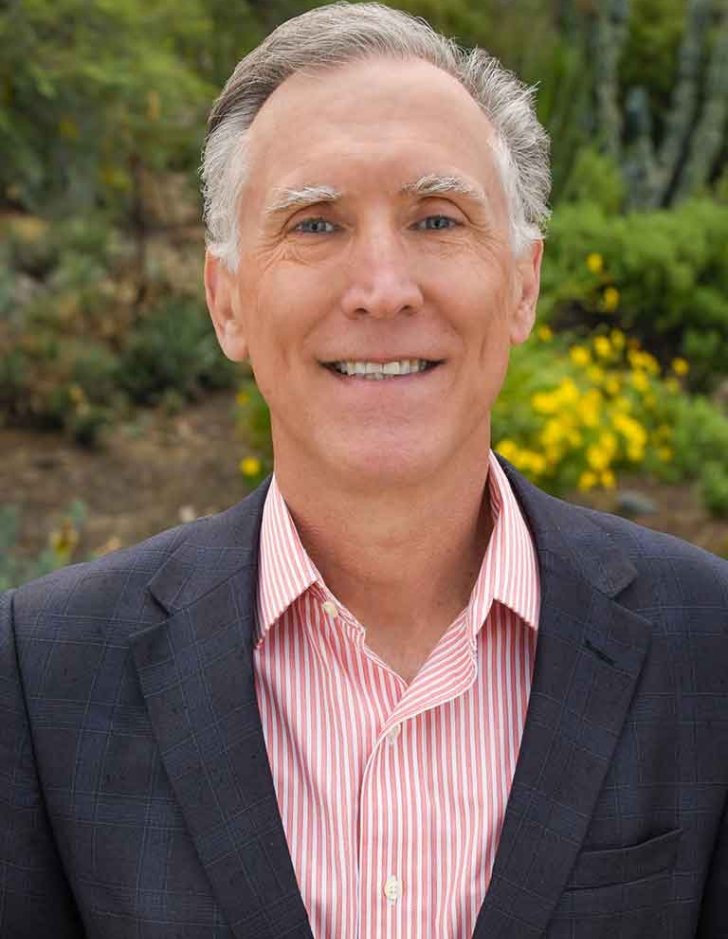

President Strom C. Thacker

A highly-regarded political scientist and accomplished higher education administrator, Thacker took office on July 1, 2023.

President Thacker’s Bio

Presidential Initiative on Constructive Dialogue

The Presidential Initiative on Constructive Dialogue focuses on how we can talk constructively and respectfully about challenging issues in the Pitzer community and beyond.

Presidential Initiative on Constructive DialogueQuick Links

Our Staff

Meet Our StaffBoard of Trustees

Meet Our Board of TrusteesStrom C. Thacker's Inauguration

View the InaugurationLetters of Recommendation

Request a Letter of RecommendationKnow Your Rights Training

View the recording and transcript of the Know Your Rights online training that took place on April 16, 2025.