Excerpted from OnlySky

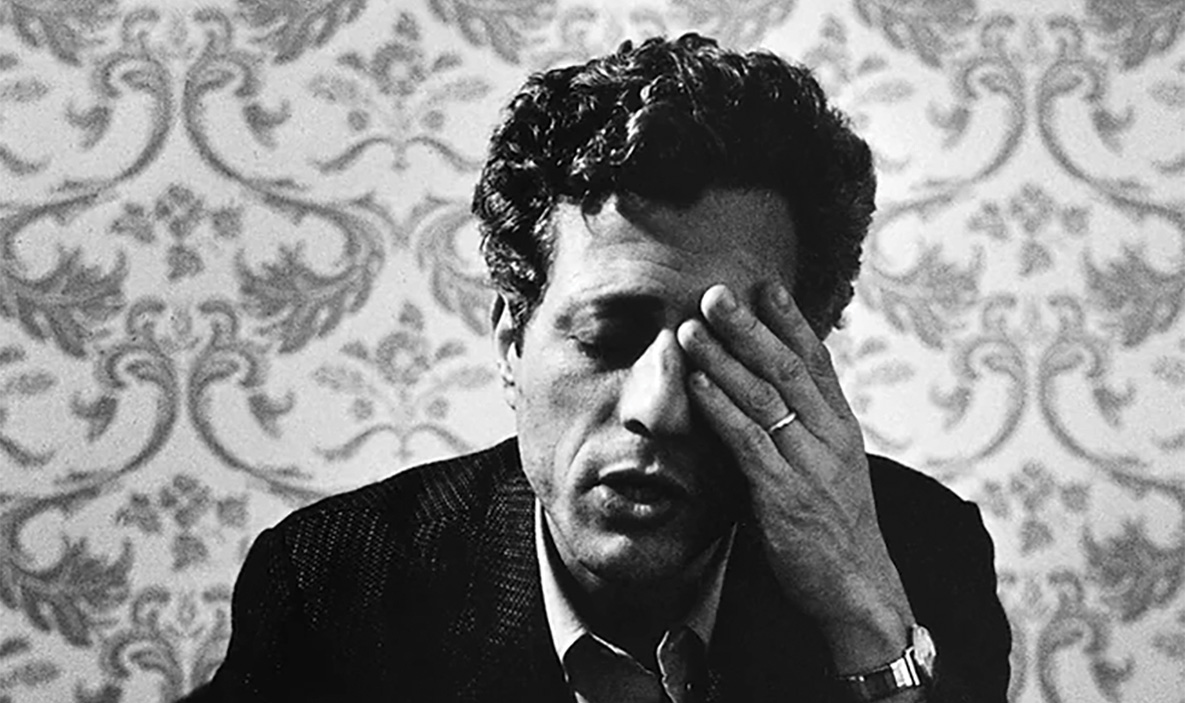

By Azamat Junisbai, Professor

Growing up, we were always taught that Russia’s presence in Central Asia was a generous gift of modernity and civilization. The word “colonialism” was never used. To this day, describing Moscow’s control of Central Asia as Russian colonialism is likely to generate irate responses from even otherwise liberal Russians, or at least a tinge of disappointment about the lack of gratitude for “roads, schools, and hospitals.”

In contrast, our curriculum omitted mention of Soviet nuclear testing carried out on Kazakh soil, Stalin-era purges of the Kazakh intelligentsia, the Aral Sea ecological disaster, or even the catastrophic man-made famine of the early 1930s in which an estimated 40% of Kazakhs starved to death.

Since Russia’s attack on Ukraine, I have been increasingly circling back to the uncomfortable memory of contempt for most things Kazakh that I had felt growing up. I associated Kazakh language and culture with being rural and uncultured. Low status. I was quick to label Kazakhs who spoke accented Russian as mambety—an insult that makes me wince today. Looking back, I can see that it was a derogatory term I reserved for those whose connection to the Kazakh language and culture has not been severed as my own had been.

It seems that Moscow’s long rule in Central Asia extended far beyond political and economic control or even erasure of language and culture. I didn’t just lose Kazakh language and culture: I learned to feel contempt for them, to be embarrassed by them. I have an uncomfortable childhood memory of thinking how strange and awkward it was that in the Kazakh language the word for “palace” is sarai which corresponds to “barn” in Russian.

It is clear that Ukraine’s heroic struggle against Russian aggression as well as the clear and present danger of the Kremlin’s neo-imperial ambitions toward Kazakhstan have rejuvenated my own sense of Kazakh identity.

-Azamat Junisbai

I suppose this is precisely what a thorough colonization is supposed to accomplish. Internalized racism is a term that comes to mind. Another is colonized conscience. Or even self-hatred or self-loathing. Coming to terms with the depths to which my own conscience was colonized is painful.

I am still trying to process this as I write, but it is clear that Ukraine’s heroic struggle against Russian aggression as well as the clear and present danger of the Kremlin’s neo-imperial ambitions toward Kazakhstan have rejuvenated my own sense of Kazakh identity as nothing ever has.

I am starting Kazakh lessons this fall. And I hope that my daughter, born in June of 2022, will grow up proud of her Kazakh heritage. Maybe this is what the beginning of decolonization of consciousness feels like.

A professor of sociology, Junisbai was born and raised in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. In this excerpt from a fall 2022 commentary for OnlySky that is reprinted with permission, he recalls how Kazakh culture and language were minimized in school and how cultural self-loathing has been one of the numbing legacies of Soviet imperialism. Read the full piece here.

A professor of sociology, Junisbai was born and raised in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. In this excerpt from a fall 2022 commentary for OnlySky that is reprinted with permission, he recalls how Kazakh culture and language were minimized in school and how cultural self-loathing has been one of the numbing legacies of Soviet imperialism. Read the full piece here.