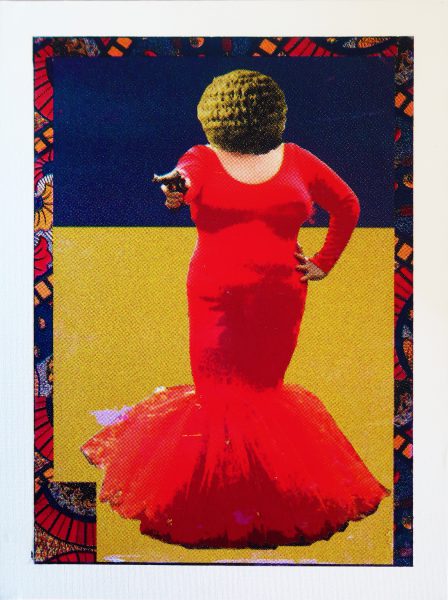

White Fetish #1 (devotional) (2018), 5 x 7.5 x 4 in.

She who tames the wild beast

Maleficent nourisher you open the door to life.

Benevolent slayer, you impress on us thy grievous wrath.

Water us, your horses, from sea to shining sea.

We will drink from the river of forgetting

Cleansed in white garments, and lose ourselves in you.

Give us our names,

Our daily offerings

And defend us, your warriors,

As we destroy those who war against you,

Lead us not into the wilderness,

But deliver us in painless labor