Chaos Arising (2017)

Collage of magazine cuttings on paper

10 x 9 ½ in.

Manifesto: A Moderate Proposal

Curated by Ciara Ennis and Jennifer Vanderpool

Chaos Arising (2017)

Collage of magazine cuttings on paper

10 x 9 ½ in.

Hold This Earth Tightly with Both Hands (2017)

Tempura and fabric on construction paper

14 x 21 ¾ in.

POW (2017)

Tempura on fabric

22 x 27 in.

Rise Up like the Birds (2017)

Tempura on fabric

22 1/2 x 21 ¾ in.

About Cure Park (2017)

On Saturday, October 28, 2017, the Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings filled the streets of Amsterdam. This performative march, initiated by Russian artist Gluklya and TAAK, brought together refugees housed in the center for asylum seekers at the former prison Bijlmerbajes, artists and everyone who feels involved, in a grotesque carnival.

The Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings resulted from a series of workshops and meetings Gluklya had with refugees in her studio in Lola Lik, a creative hub in the former prison Bijlmerbajes, situated next to AZC Wenckebachweg. These sessions where aimed at trying to find new visual forms of expression for emotions which are difficult to convey because of language barriers. During the preparations for the festival, costumes, masks, music and objects were developed, expressing fear, vulnerability, loneliness and what it feels like to live in a former prison. With this carnival, we do not only want to make a powerful statement about welcoming refugees, but also give refugees a face and a voice in the public domain.

Cure Park

The intention of Cure Park was to invite artists, professionals and public to actively contribute to mutual learning and sharing knowledge and experiences tojointly explore what it means to take care of yourself, others and the environment. What happens when yougive orreceive care, what are the conditions, who decides, what questions are asked and what are the questionsthat we often shy away from when speaking in public.

Timely physical and mental spacesdesigned by artist, where sickness, accident, traumaand all that what makes us different are allowed to exist, providedsecurity to open up to each other and confront us with different states of being and experiencing the world. Care giving and receiving as a common ground for exchangeon spiritual, emotional, mental and economical level.

We believe that artists work towards the futurewith reality as their raw material.

Art as a form of “thinking by doing” presupposes social commitment combined with uncertainty and flux and that makes the practice of art suitable as a model for other fields of knowledge and valuable in conjunction and cooperation with this, (read care).The purpose is to emphasize the real problematics on an individual level when we are confronted with illness and care and think together around it’s economical, political, social and spiritual dimensions, to enable us to acknowledge shared concerns.

We see the arts as a healing practice by not isolating the problem but to understand it as a part of a bigger whole.

Inspired by The Undercommons as introduced by Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey, starting form the notion that prosperity today isunderstood in the lightof the mechanisms of control: the spread of capitalist logistics, control and management of care. Mechanisms that not only shut out the ‘underprivileged’but also do not recognize the injustice it creates.

The goal of CP wasnot to end problems, but to change the world thatcreates the problems. That requires a different order of things, a different logic. Releasing antagonism and forms oflabeling, replaced by thinking in terms of dialogue, connecting people andinitiatives that do not partakeinto the current discourse and are therefore not heard. Thisis something that can be practicedas anongoing experiment, a way of doing and being together with others without a fixed place and time.

WithinCure Park, art has been conceived as a practice howtoshape methods and create the conditionsfor a meaningful exchange between artists, professionals and the public. Together we formulated questions that really matter, while experimentingand conductingmany forms of being together, working, guiding, listening, touching, speaking, feeling, eating, etc.

CP was aligned with the ideas of Degrowth from the late sixties, when a forum of economists, scientists and politicians advocated a world that is not dominated by growth, but in which other values prevail, maximize happiness and well-being through non-consumptive means—sharing work, consuming less, while devoting more time to art, music, family, nature, culture and community.

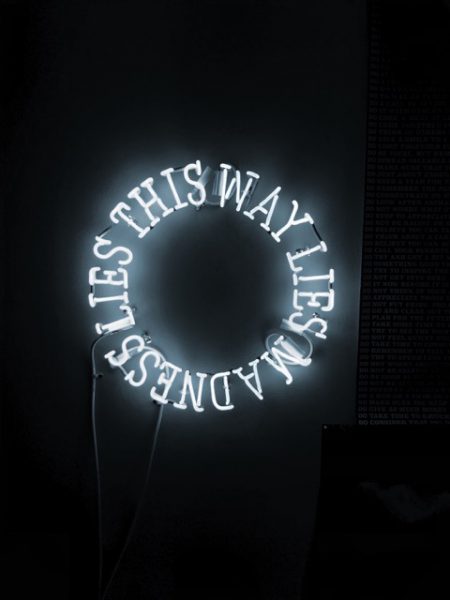

This way lies madness is an excerpt from King Lear. In this quote from Act 3 of Shakespeare’s tragedy Lear is considering his madness. We changed the quote so that it reads This way lies madness lies. The looping of this statement, the circle, acts like a tautology. It is a repetition that one gets caught (up) in and can’t see outside of, and in this way it mimics confirmation bias and the tribalism that has infected society. The form itself acts as a portal, which narrows one’s focus.

Lear’s madness increases over the course of the drama and in this statement Shakespeare emphasizes how obsession over a worry or point of view can cause one to forget everything else. Our piece expands on this point through both its form and the multiple meanings that can be read into it. In effect it is an anti-manifesto, which is meant to encourage one to escape the “madness” of insular ideology.

The text is adapted from Shakespeare’s tragedy King Lear. The original quote and context is:

No, I will weep no more. In such a night

To shut me out? Pour on; I will endure.

In such a night as this? O Regan, Goneril!

Your old kind father, whose frank heart gave all—

O, that way madness lies; let me shun that;

No more of that.

King Lear Act 3, scene 4, 17–22

Map to CIW (2017)

Printer paper

8 ½ x 11 in.

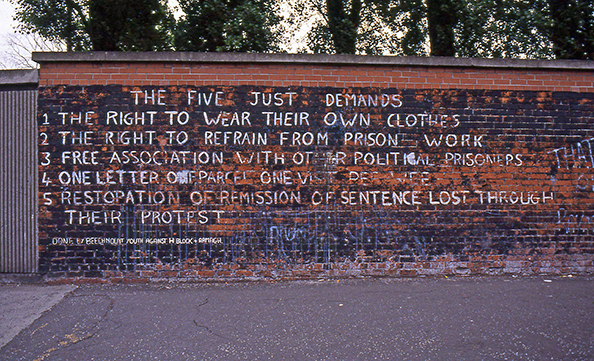

The Five Just Demands appeared in 1981 in Beechmount Avenue, Beechmount, in Irish Republican West Belfast. Painted by local youths, though organized by Sinn Féin, the political wing of the Irish Republican Army, this was an early example of what became a tradition of political muralism that continues to the present. The mural itself articulates the five demands that were the basis of the 1981 Hunger Strike in which ten Republican prisoners died. The demands were part of a bitter prison struggle provoked by the British government’s decision in 1976 to revoke ‘Special Category’ status (in effect Prisoner of War status) for those convicted of a violent offence committed for political purposes, and to treat such offenders as criminals. Viewed in that context, though the five demands were relatively innocuous, the campaign to achieve them amounted to nothing less than the contestation of the legitimacy of the British State in Northern Ireland.

This mural was painted in Rockmount Street, off the Falls Road, in Irish Republican West Belfast; it was sponsored by the Sinn Féin Trade Union department. The mural commemorates James Connolly, one of the central figures in the Irish Republican socialist tradition who served as a Trade Union organizer in Belfast and contested a local election in 1913. More importantly, Connolly was a leader of the 1916 Rising in Dublin against British rule and one of the seven signatories of the ‘Proclamation’ of the Irish Republic; he was executed after the defeat of the Republican forces. In 1907 Connolly penned a satire on reformists which included an ironic retort to their appeals for the moderation of the program of the Irish socialists: ‘For our demands most moderate are, we only want the earth.’

Gentrification is Displacement and Replacement of the Poor for Profit Syllabus by School of Echoes (2017)

Printed words on paper

11 x 8 1/2in. (Two documents)

Ultra-Red / School of Echoes Broadsheet – School of Echoes (2017) Anti-Gentrification Syllabus