ANTARTICA

November 17, 2007 – January 12, 2008

Nichols Gallery and Lenzner Family Art Gallery

ANTARCTICA brings together three extraordinary series of works from artists Joyce Campbell, Anne Noble, and Connie Samaras on the subject of Antarctica, the most extreme continent on the planet. Recipients of distinguished artist residencies — Campbell and Noble awarded the New Zealand Artists to Antarctica program and Samaras the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Artists and Writers Program — enabled them to photograph and experience first hand the severe and almost inhuman conditions of Antarctica. Each artist’s work approaches the subject with differing yet overlapping critical frameworks creating a rich transcultural dialogue that seeks to de-exoticize a landscape that has been romanticized, idealized, and made epic.

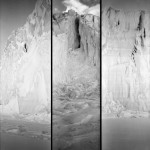

With their physically immersive scale and unique objecthood, Campbell’s photographs are formulated to be historically and physically compelling objects rather than images of places or things. Campbell approached Antarctica as something vast, savage, and primordial. She used anachronistic photographic technologies including Daguerreotype, that was outmoded by the mid-nineteenth century invention of silver halide emulsion and which had never been practiced on that continent before.

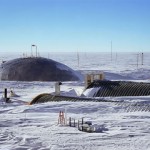

Samaras’ photographs, Vast Active Living Intelligence System, shot at the South Pole as well as her videos shot in other Antarctic locations, depict the liminal space between life-support architecture and extreme environment. Interested in ideas of speculative landscape, science fiction, psychological dislocation, and the political geographies underpinning fantasies of space exploration, her work frames the paradoxical relationships inherent in attempts to colonize a space resistant to human habitation.

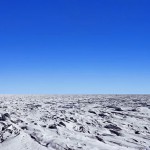

Since 2002, Anne Noble has been considering the cultural origins of the Antarctic imaginary and how this contributes to a sense of place. Her project Whiteout explores representation of the landscape at the point where perception and cognition founders. In other projects, whether from the decks of Antarctic tourist ships or traveling around to the world to photograph dioramas of Antarctica, she critiques the framing of the Antarctic landscape as picturesque, heroic and sublime.

Essay – “The Wondrous Cold”

I don’t know when Taff died…a week ago, a month. It was somewhere up on the glacier. I know that the day before we’d got into a frightful pickle. Scott said it was our own fault. We’d started out in a wretched wind, pulling on skis in a horrible light that threw fantastic shadows across the snow. Birdie said he was reminded of a pantomime set for Ali Baba and the forty thieves, all glittering backcloths and eerie pockets of stagy darkness. As far as I could tell the world was a coffin and the lid of the sky was about to nail me done. It showed up the difference between us, but then I don’t imagine Birdie’s feet were in the first stages of gangrene.

–Beryl Bainbridge, The Birthday Boys (1991)

Much of what we know of Antarctica—the continent most extreme and inhospitable to humans—is informed by its dramatic associations, the wide-eyed wonderment, and the toe-curling terror. Divided, almost biblically, into one long day and one long night, it has no human residents, only visitors, and an extremity of weather that reaches -130 °F. It is no wonder that Antarctica has spawned a host of accounts, both fictional and authentic, and driven generations of seekers to a place that feels like the end of the world. Artists Edgar Allen Poe and Howard Hawks set narratives there and explorers Roald Amundsen and Ernest Henry Shackleton recounted their adventures. Compelled by their own investigations, artists Joyce Campbell, Anne Noble and Connie Samaras—each awarded artist residencies—journeyed there in an attempt to query established representations of the coldest place on Earth.

The Artic has an annual mean temperature of 0°F. The Antarctic’s correspondent temperature is -58°F. Had Mary Shelley been born a hundred years later she would have banished “The Creature,” Dr. Frankenstein’s monster, to the south instead of the comparatively mild north. In a similar sleight of history Joyce Campbell’s series of works entitled Last Light (2006) uses both the daguerreotype—a photographic process that had become obsolete by the time of the Antarctic expeditions—and mural-scale, silver gelatin prints, that present Antarctica’s natural architecture in full Gothic force. The romance of the daguerreotype also renders Campbell’s work reminiscent of the romanticism of the Hudson River School landscape painting, particularly Edwin Church’s The Icebergs (1861), that celebrated the exquisite grandeur of largely unconquered territory. The massive glaciers, vertical and jagged, distorted from premature erosion wear their fissures like gruesome masks. Campbell’s deliberate use of an anachronistic technique makes hers the first such photographs to exist of the Polar Regions. Initially these brutal yet spectacular images can’t help but allude to the “Heroic Age of Polar Exploration” (1895-1917) and Captain Scott’s ill-fated (some say vainglorious) race to the South Pole. In another chronological turn, however, the images focus instead on a landscape that is clearly wounded from the exponential effects of climate change––suggesting that unless we radically amend our irresponsible ways that we, like daguerreotypes, will be rendered obsolete.

n contrast to Campbell’s Gothic inspired imagery Anne Noble presents an abstracted but similarly bleak view of Antarctica. White Out (2002–2007)—a series of twelve works closely configured in a tight grid, depicts the exquisitely treacherous moment of a blizzard when visibility is limited to a shroud of raging white particles and the distinction between sky and ground is erased. In this way Noble’s White Out series recall the more abstract of Hiroshi Suigimoto’s somber and minimal seascapes that by merging the sea and sky produced subtle grey monochromatic images. Inspired in part by the Erebus disaster of 1979—an Air New Zealand sight-seeing tour that crashed into Mount Erebus during a white-out killing all 257 aboard—Noble presents a study of the tones, textures, and layers of whiteness, their abstract nature defying immediate interpretation and recalling 60s post-minimalist Robert Ryman’s ground-breaking and influential series of white-on-white canvases. Taken out of context these entrancing yet perplexing photographs offer an alternative to the conventional framing of Antarctica as heroic, romantic, and sublime providing instead a less than comfortable image. Similarly, Goal Post (2002), from the series From Place to Place, depicts what looks to be a massive capital “H” in the center of a bleak snowy landscape stretching for miles. Devoid of human trace, the goal post is transformed into a gateway to nowhere, a redundant gesture prophesying a future of desolation and doom.

Contrary to Campbell and Noble’s lonesome and immersive landscapes, Connie Samaras pictures the life-support architecture that makes human habitation possible. As a temporary resident of Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, one of the only permanent year-round research facilities, Samaras took a visual inventory of partially submerged, abandoned, and operational structures—pods, domes, and tunnels. Grouped under the collective title VALIS (vast active intelligence system), after Philip K. Dick’s 1981 science fiction novel of the same name, Samaras’ images forecast a bumpy and preternatural future—thirty years being the average lifespan of a building before it becomes irretrievably submerged by blowing and drifting snow. Dome Interior (2005 -2007), depicts the abandoned sleeping quarters of one such structure. Resembling meat lockers or morgue drawers, the rows of vacuum-sealed metal doors reflect the snow-covered wooden platform supporting the bright red rectangular units, all under the roof of a shiny geodesic dome. Forlorn and derelict, the scene evokes Roanoke’s lost American colony or the prologue to many science fiction films. Antarctica’s hostile environment is similar in many ways to how we naively imagine the landscape of other planets—extreme and uninhabitable. Samaras’ work suggests that conceit and alludes to the inevitable futility of colonizing such a place. The huts of explorers like Scott and Shackleton survive there yet, as rigid monuments to ambition and tragedy.

In their varied stylistic approaches Campbell, Noble and Samaras could be said to represent past, present and future views of Antarctica. Campbell’s deliberate use of anachronistic techniques and allusion to early twentieth century themes critique the romantic and heroic mythos of the noble Polar explorer and are contrasted with Noble’s bleaker view of the present. Noble’s deadly white-outs and displays of the barren Antarctic landscape reveal how our experience of place is relentlessly mediated and constructed. Alternatively, Samaras suggests an alien and dysfunctional future where the drive for survival dictates a bizarre civilization of transience occupying but never inhabiting. Campbell, Noble and Samaras use romance, mystery and fascination to present works whose exquisite formal beauty veils the foreboding and catastrophic subtext that infiltrates their work.

Ciara Ennis

Director/Curator, Pitzer Campus Galleries

WORLD IS WATCHING – MANIFESTO

WORLD IS WATCHING – MANIFESTO