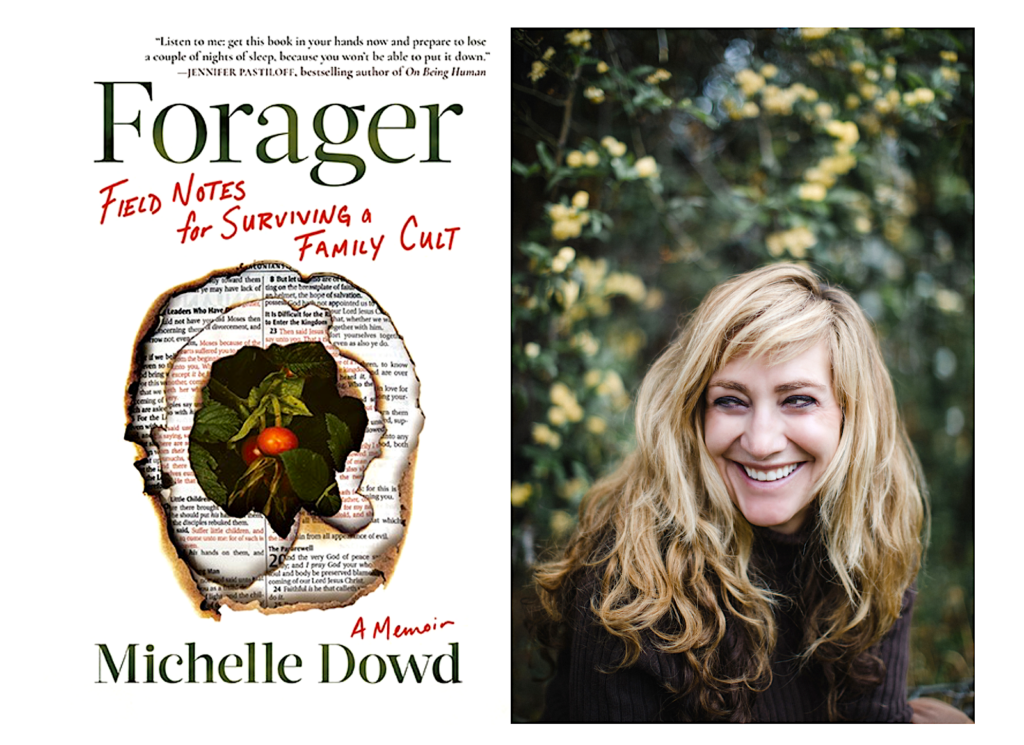

Lessons learned: In her acclaimed memoir, Michelle Dowd ’90 looks back on being raised as a member of the Field and how she was finally able to leave.

Lessons learned: In her acclaimed memoir, Michelle Dowd ’90 looks back on being raised as a member of the Field and how she was finally able to leave.

Claremont, Calif. (March 29, 2023)—The opening sentence of a book can be unforgettable. Anyone familiar with Melville’s Moby Dick knows it famously starts with “Call me Ishmael,” while Ray Bradbury begins Fahrenheit 451 with a simple confession: “It was a pleasure to burn.”

The same is true of the opening sentence of Forager: Field Notes on Surviving a Family Cult, a memoir by Michelle Dowd ’90:

I grew up on a mountain, preparing for the Apocalypse.

That sentence is unforgettable. And hardly an exaggeration.

Recently published by Algonquin Press, Forager recounts ten years of Dowd’s childhood growing up in a cult called the Field and on a 16-acre plot she calls the Mountain located in the Angeles National Forest (on the San Andreas Fault no less). The book is a survivor’s testament; a memoir harrowing at times but ultimately triumphant and (from that first sentence) thoroughly engrossing.

There are a lot of us out there, and we think we’re fine until we’re not.

Michelle Dowd ’90, author of ‘Forager’

Dowd explains in her memoir that though she foraged daily for edible plants on the Mountain, her real home wasn’t a place but an idea, one that her maternal grandfather turned into the Field, a closed community into which she and her mother were born.

Of this community Dowd writes in her book:

Both Field and Mountain were governed by Grandpa, the ruler of our world. Grandpa said he was God’s prophet and would live to be five hundred years old, that the angels would descend from heaven and take him up into the clouds like Elijah. Grandpa’s followers believed every word he said, because at the Field, he was the only one with authority. His pontifications were the soundtrack of my childhood, and his sincere belief that God’s vengeance would be unleashed upon the world unless a small group of God’s chosen people stayed his hand terrified me.

“My grandfather decided the truth, and he lied all the time,” Dowd explained in a recent interview. “He lied to his own sons about when he was born, that he had a degree from Berkeley and a PhD from Stanford. He never went to college. Everyone in the Field called him ‘Grandpa,’ so I didn’t even know as a kid that he was my biological grandfather. It was confusing, and I never really trusted myself. If I ever asked my mom questions, she would just shut right down.”

It’s not surprising that one of the lasting effects of growing up in a cult is trauma, something that she confronted years later in therapy.

“There are a lot of us out there, and we think we’re fine until we’re not,” Dowd said. One of the biggest issues she had to reckon with was the realization that her parents didn’t love her or her siblings. “They couldn’t express love in any way that any of us could feel. They gave us up right at our births to the collective. They didn’t nurture us; didn’t hug us or say ‘I love you.’ I felt that lack from a very early age.”

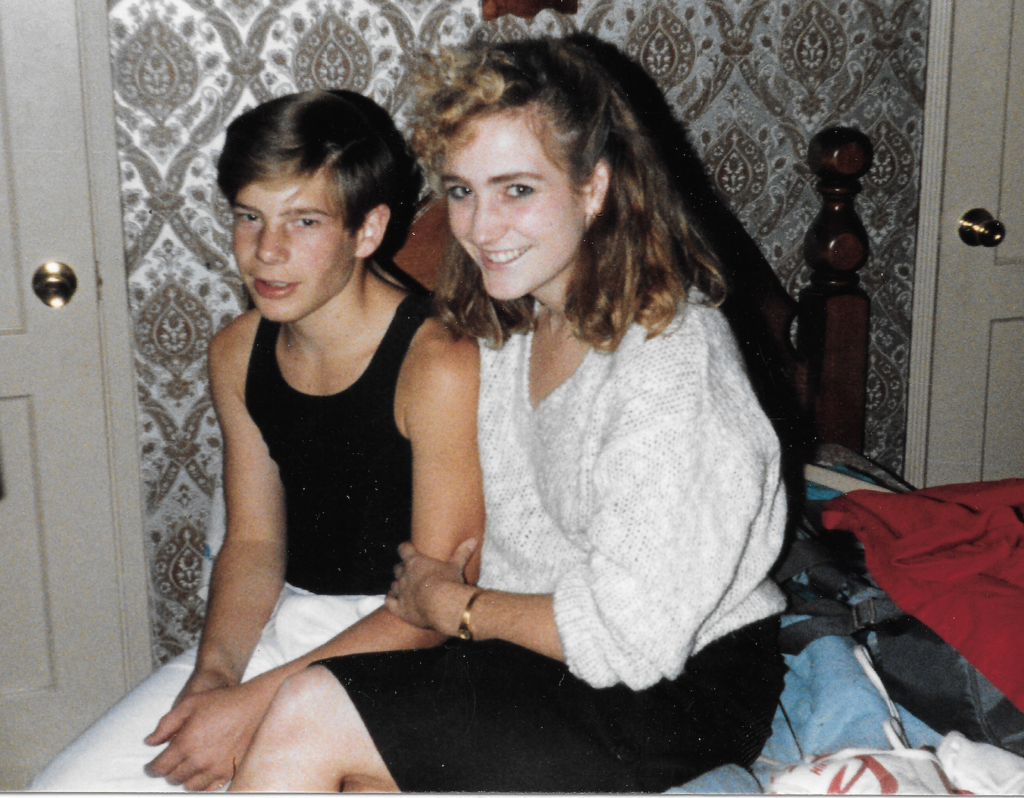

Brother and sister: Dowd with her brother (called Danny in Forager) in 1986. Few photos exist from the earliest years of Dowd’s childhood. This one was taken right before she arrived at Pitzer College.

Brother and sister: Dowd with her brother (called Danny in Forager) in 1986. Few photos exist from the earliest years of Dowd’s childhood. This one was taken right before she arrived at Pitzer College.

An Unexpected Glimpse

of the Outside World

A seminal event in Dowd’s early life occurred at the age of 10 when she entered Children’s Hospital Los Angeles for symptoms that might have been chickenpox. At the time, Dowd was the first child of a leader to ever leave the confines of the cult.

“Every single person in my mom’s family lived there their whole lives,” she said. “They died there. My mom never had a job in her life. We didn’t have Social Security numbers, income, or pay taxes. Accountability eventually happened because computers were invented.”

Ironically, or perhaps inevitably, it took Dowd’s hospital stay to begin to give her a sense that there were different places in the world. The chickenpox diagnosis soon led to an extended stay in isolation when it was discovered she had Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, a condition in which the immune system mistakenly attacks platelets and requires bone marrow transplants.

Through the many months of treatments, Dowd’s mother was her only visitor and her visits were infrequent.

“I felt like I was going to die abandoned and alone,” Dowd said. “But when I got back to the community, there was a part of me that had shifted.”

Once back at the Field, Dowd found that her grandfather had scapegoated her with accusations that she had gotten sick because there was evil in the community and, worse still, that Dowd might have been the Antichrist or the wicked Jezebel of the Old Testament.

“But I didn’t think he was crazy,” Dowd said. “I thought I might have been Jezebel. For sure there was shame about me being sick. My mother was so embarrassed that she never told people. To most of the Field, I had just disappeared.”

Starting a New Life: Pitzer and Beyond

When she was 17, Dowd made her escape and “disappeared” from the cult, enrolling at Pitzer in 1986.

“At Pitzer, people would ask me where I came from and where I went to high school,” she said. “I didn’t go to high school, of course. It was uncomfortable, and I’d say I was home schooled. I just couldn’t talk about it. I didn’t know any contemporary music, television, movies. I didn’t have a way to relate.”

According to Dowd, she didn’t choose Pitzer, Pitzer chose her.

“I didn’t even apply to the college,” she said. “Somebody sent my application, which I had written with a pencil, to Pitzer, and they sent me a note saying they received my application from another school and that they would like to offer me funding to come to Pitzer. I was scared to take out loans and owe money. I really didn’t know what I was doing.”

After Pitzer, Dowd earned a graduate degree at the University of Colorado at Boulder and is currently a journalism professor at Chaffey College in Rancho Cucamonga.

Resilience and

a Sense of Community

Dowd’s mother never apologized to her for the neglect she experienced during her childhood, but Dowd believes her parents were both brainwashed. Regardless, she credits her mother, who was a skillful naturalist, with giving her survival skills, the most important one being resilience.

“I’ve been told my whole life that I’m resilient,” she said. “I think the skills my mom taught me in nature—how to look around and make do with what you have—are important. There is always something you can use and you’re never helpless. She taught me the opposite of helplessness. She taught me agency; that I should never rely on anyone but myself, and self-reliance is a skill.”

Another qualified “positive” that Dowd sees coming out of living in a cult is that members have a rich sense of community.

“I learned very young that family didn’t need to be blood and that you could really have each other’s backs,” she said. “In the Field we used the word ‘unity’ a lot. It was almost like we were cheerleaders for the concept. We moved as one and everyone had a role to play. While that can hamper your personal development, it’s also incredibly useful to know how to collaborate.”

Listening to Herself

Dowd wrote Forager in four months during the pandemic and while working full time. Despite the many startling incidents in her life as a member of the Field, she says she didn’t want to pummel the reader with “drama porn.”

“I came from a family that didn’t own a camera,” she said, musing that there aren’t any images of herself as a child. In her book, Dowd compensates for that by painting word pictures that are as crystalline as any photograph.

“I was almost unable to talk about my past my whole life,” Dowd said.

Illumined by the flickering light of a single candle, she sat in darkness writing Forager by hand.

“I just channeled the young girl inside of me,” she said. “No one had ever listened to her. I just sat and ‘listened,’ and her story just flowed out of my hand.”

- Meet the author: Michelle Dowd ’90 will talk with Sociology Professor Phil Zuckerman about Forager at a special author event held April 27 on campus. The event is free and open to the public. Get more information.