A roundup of new and recent books by Pitzer College faculty

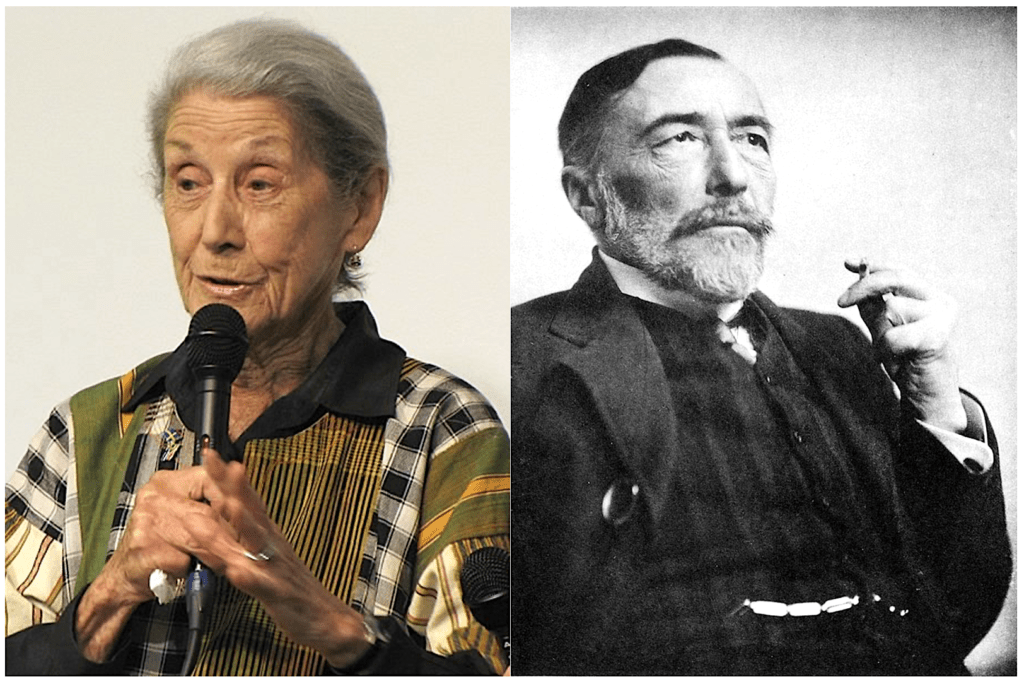

Colonialism’s legacy: Amanda Lagji explores the works of Nadine Gordimer (left), Joseph Conrad (right), and others in her new book Postcolonial Fiction and Colonial Time: Waiting for Now.

Colonialism’s legacy: Amanda Lagji explores the works of Nadine Gordimer (left), Joseph Conrad (right), and others in her new book Postcolonial Fiction and Colonial Time: Waiting for Now.

If you’re an admirer of Joseph Conrad’s story Heart of Darkness, you know that Marlowe, the narrator, takes a long time to get to the point.

He unwinds a long yarn about his travels up the Congo and his quest to find the elusive Kurtz, and his listeners (and readers, too) must wait until nearly the end to learn the legendary ivory trader’s fate.

This experience of waiting isn’t just a powerful element in Conrad’s story. Other stories written by authors living on the African continent today evoke waiting as a significant theme, which Amanda Lagji makes the central focus of her new book Postcolonial Fiction and Colonial Time: Waiting for Now, which has been published by Edinburgh University Press.

An assistant professor of English and world literature, Lagji received her doctoral degree from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst—and you might expect that she would have wanted to focus on the works of Emerson, Thoreau, Dickinson, Hawthorne, Melville, and other New England giants.

But the literature of New England interested her less than what African writers like Nadine Gordimer, J.M. Coetzee, Zakes Mda, and many others were doing in their work.

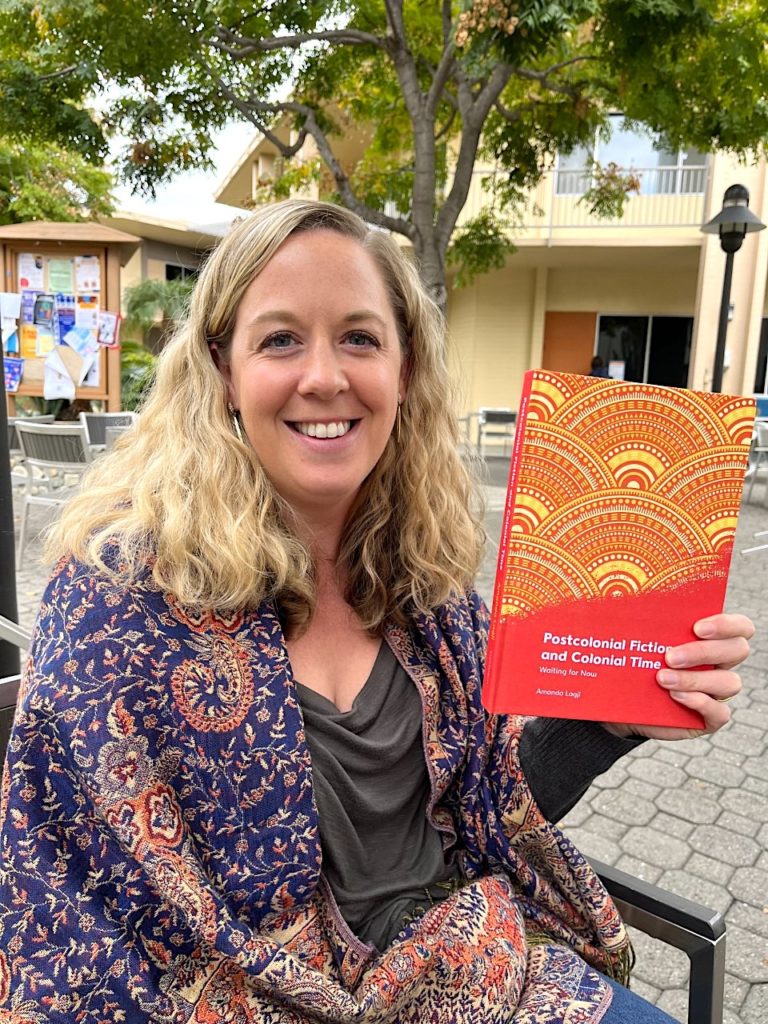

Assistant Professor of English and World Literature Amanda Lagji

Assistant Professor of English and World Literature Amanda Lagji

“When I was in school and on a fellowship studying abroad, I became really interested in power and language, gender and identity,” she said, “and the work of these writers felt like it was speaking in a more urgent way than what I or any other student was typically reading.”

Originating in her dissertation, Postcolonial Fiction and Colonial Time argues that waiting is a fundamental element in understanding time and power in postcolonial fiction.

Starting in the 1950s, African nations tasted liberation as they transitioned from colonized governments to independent states. But the excitement and celebration soon waned into disillusionment and stagnation—and this stagnation takes the shape of waiting in the fictional works that Lagji analyzes.

The book’s starting point is Conrad and takes readers through various works by Gordimer, V.S. Naipaul, and others that wrestle with the legacy of colonialism and the challenges posed by independence, especially what Lagji calls “a lasting preoccupation with waiting and stasis.”

“The euphoria of independence was soon replaced by the feeling that everything had stalled. That there was no movement, no progress, to get anything done,” she explained.

Waiting, though, isn’t always negative. Lagji said that in the U.S., protests after George Floyd’s murder or in response to other social inequities have disrupted institutions and forced them to suspend operations (to wait, in other words). When that happens, there’s a chance to have dialogue and real change. Waiting, she said, “can have a power of its own when it is put in service to something else.”

Critics have praised Lagji for this perspective, including the University of Adelaide’s Andrew van der Vlies, who writes about Lagji’s new book that it “presses reset on our tendency to read waiting as stasis, instead recasting apparent impasse as productively disruptive to hegemonic temporalities. A timely and important work.”

Visiting Assistant Professor Chris Willoughby

Visiting Assistant Professor Chris Willoughby

In 2000, the publication of the book Taboo by a sports journalist created much controversy by arguing that Black athletes are better at sports because they are genetically different.

The book became a source of contentious public debate, but its insistence on genetic differences was hardly an isolated example.

Many false ideas about biological differences continue to be found, and none of it is surprising to Christopher Willoughby. Or new.

“People don’t just wake up one day and start racializing other people,” said Willoughby, who is a visiting assistant professor of the history of medicine and health at Pitzer. Willoughby is the author of Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools, which has been published by the University of North Carolina Press. “There’s a long chain of transmission behind such behavior, and my book tries to trace that chain and find some of its origins.”

Hailed by Harvard historian Vincent Brown as “a meticulous autopsy of a ghoulish intellectual scandal,” Willoughby’s book powerfully examines the deeply problematic area of how racial theories distorted medical education in 19th-century America. Willoughby reveals how ideas about anatomical differences became accepted in medical schools not by some extremist or fringe group, but by some of the leading mainstream figures of the day.

That includes Joseph Leidy—one of Darwin’s greatest American followers—who saved countless lives with his breakthrough discovery of the parasite causing trichinosis. Leidy was regarded as one of the most prominent paleontologists in the U.S. in the second half of the 19th century. What’s lesser known is that Leidy also believed, Willoughby said, that “there were more differences between Black and white people than there are between lions and tigers.”

Leidy never wrote that comment in any book, though. You have to look at what his students wrote about him in their own notes and academic works. That’s just what Willoughby did, and it’s one of the reasons why this book is a pioneering work. Willoughby pored over the dissertations of some 4,000 medical students to uncover such views and other ideas about race and medicine that he calls “just terrible.”

That includes “drapetomania,” a hypothesized mental illness that supposedly caused slaves to run away from their masters. Medical practitioners of the time believed that slavery was such an improvement on the lives of slaves that only a mental illness could explain why anyone would want to escape.

Willoughby’s book also shows the medical establishment’s significant hypocrisy when it came to experimentation. Despite a belief in the biological differences between races, medical practitioners didn’t hesitate to dissect the cadavers of Black people to help them understand bodily functions.

“That’s one of the great ironies and great mysteries that scholars find when they look back at that time,” Willoughby said. “There was never anyone who tried to explain this contradiction of dissecting a body to improve our medical understanding and yet saying that it belongs to a different species.”

Masters of Health may be a history, but he doesn’t treat his subject as something locked away in the past. The chain of ideas that he finds in 19th-century medical schools has wound its way into the 20th century and reaches to the present day.

Willoughby hopes his book will serve as an important response to this.

“If we can explain where these ideas have come from, if we can understand this better, maybe we can break that chain. Maybe more people will be inclined to abandon them,” he said. “It’s not just incredibly disturbing to see how much these ideas are still around in the non-medical population, it’s also frustrating that they are still yet to be eradicated from medical education. I want my book to assist with that. I want it to be a wakeup call.”

Learn more about Willoughby’s new book at University of North Carolina Press

Professor of Linguistics Carmen Fought

Professor of Linguistics Carmen Fought

“Disney works very, very hard to present itself as wholesome, sweet, innocent family entertainment, [but] there are some really dangerous messages in here.”

That’s linguistics professor Carmen Fought describing her new book Language and Gender in Children’s Animated Films co-authored with alumna Karen Eisenhauer ’13 and recently published by Cambridge University Press.

Disney and Pixar might be beloved by audiences of children and adults, but what kinds of messaging do we find in the characters and stories created by these media giants?

Fought and Eisenhauer apply in-depth qualitative analysis to examine biases in scripted language as well as how femininity, masculinity, and queerness are treated. The authors felt that linguistics would provide a good way to measure how these movies portray male characters, female characters, and queerness in their films.

Fought began writing the book with Eisenhauer, who had been her student, research assistant, and project manager in the past, in 2020. Each author handled half of the chapters with a goal of making the language appeal to both their peers in the discipline as well as to lay readers.

In the process, according to the publisher, the authors have demonstrated “how different linguistic tools and techniques can be used to better understand popular children’s media.”

This fall, The Student Life talked to Fought about the new book. Visit here to read the full interview.