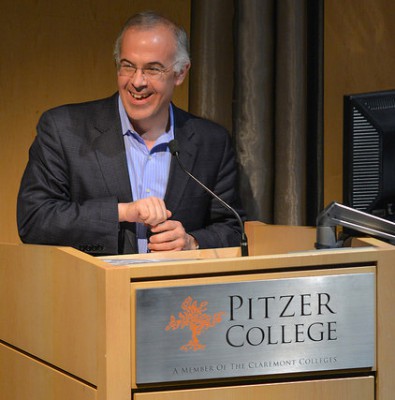

David Brooks P’16

David Brooks P’16

President Laura Skandera Trombley: It’s wonderful to see all of you here this afternoon and, yes, you’re absolutely in for a treat! David is a talented political and cultural commentator who has been an op-ed columnist with the New York Times since 2003, he’s worked as an editorial writer and film reviewer for the Washington Times, a reporter and op-ed editor for the Wall Street Journal Times, a senior editor at the Weekly Standard, a contributing editor at Newsweek and the Atlantic Monthly, and he’s currently a commentator at the PBS Newshour. He’s a prolific writer of books and essays and he has won many awards. However, I think his greatest accomplishment is that he is a proud Pitzer parent and father of Naomi. [Clapping]

He is known for his humor and intellectual passion and he’s a profound observer of the American way of live and savvy analyst of present day politics and foreign affairs. And he’s really one of my favorite writers and I would say that even if he wasn’t sitting right in front of me. In his book, The Social Animal, he comments about the role that educators play. He says, “The point of being a teacher is to do more than part facts. It is to shape the way students perceive the world, to help a student absorb the rules of a discipline. The teachers who do that get remembered.”

I hope that we all can remember the teacher who did that for us. I was exceptionally lucky as I went through college to find faculty who were like the faculty here at Pitzer who made an indelible impression in my life. The faculty at Pitzer will be, I hope, among your students’ favorites and a particularly talented young man, Phil Zuckerman, has recently published a book and David commented about Phil in the New York Times. This is what he said, “As secularism becomes more prominent and self-confident, its spokesmen have more insistently argued it should not be seen as an absence, as a lack of faith, but rather as a positive moral creed. Phil Zuckerman, a Pitzer College sociologist, makes this case as fluidly as anybody in his book, Living the Secular Life. So, I’m actually getting in a little word for Phil in addition to introducing David. [Clapping]

Thank you, thank you. Alright. So, since this is parents’ weekend, I thought I would close with this last quotation by David about parenting, and I will confess the first time I read this I was so relieved, I just wanted to jump up and down with joy.

David says, “If there is one thing developmental psychologists learned over the years, it is that parents don’t have to be brilliant to succeed. They don’t have to be supremely gifted teachers. Most of the stuff parents do with flash cards and special drills and tutorials to hone their kids’ into perfect achievement machines don’t have any effect at all. Instead, parents just have to be good enough. They have to provide their kids with stable and predictable rhythms. They need to be able to fall in tune with their kids’ needs, combining warmth and discipline. They need to establish secure emotional bonds that kids can fall back upon in the face of stress. They need to be there to provide living examples of how to cope with problems of the world so that their children can develop unconscious models in their heads.”

Absolutely exquisitely put. And today David will be speaking about a topic that is near and dear to our hearts: Liberal Arts education. David Brooks. [Clapping]

David Brooks P’16: Thank you Laura, it’s been a pleasure to get to know you over the past three years and sorry for it to all go downhill now. I am a proud Pitzer parent. I am now a somewhat addled Pitzer parent having seen my daughter’s dorm room about an hour ago. There are some times when you just have to close your eyes as a parent and hope it’ll go okay. Did there have to be so many bottles lying around? I will be brief, I’ve been around Pitzer long enough to know you didn’t actually come here to hear me speak, you came here to hear yourselves speak. And so, I’ll try to get out of the way of that. We actually took this great tour of Pitzer and I wanted my daughter to go to the most conservative school in America and someone told me Pitzer, it’s a Mormon school in Southern California. Pat Robertson teaches there… so it’s somewhat different than I expected. Leads the country in bumper stickers, I’ve noticed. Actually I grew up somewhat left wing. When I grew up in Greenwich Village in the 60’s, my parents were somewhat in the left. They took me to a thing in 1965 called a “be-in”. Where hippies would go just to “be”. One of the things they did was set a garbage can on fire and threw their wallets in it to demonstrate their liberation from money and material things. And I was five and I broke from the crowd, reached into the fire, and grabbed some money, and ran away. That started my first step forward to the right. Then I went to a place called Grace Church School in lower Manhattan, if anybody knows the Strand Bookstore where I was part of the all-boys Jewish choir. We sang but we were Jewish so we didn’t want to sing the word “Jesus” and we just left the word out. So the volume would drop and we would come back up. Then I had my own introduction to the liberal arts. I had it through my parents: they were college professors.

I knew I wanted to be a writer at age seven. So what this school represents was implicated early. I remember in high school I wanted to date a woman named Bernice. She didn’t want to date me, she dated some other guy. I was thinking, “What is she thinking? I write way better than that guy!” But I went off thanks to the admission committee at Brown and Wesleyan and Colombia, I went to the University of Chicago, where fun goes to die. That’s less true now to be fair. Though, the thing that is true is that the best saying about Chicago is it’s a Baptist school where Atheist professors teach Jewish students says Thomas Aquinas.

And now, because I only really teach at schools I couldn’t have gotten into. I teach at Yale, where I do teach a lot of the achievement machine kids. I wrote in one of my books, if you go to an elementary school at three in the afternoon in an urban affluent area, you got all these cars driving up, all these Saudis… all these Saabs and Audis, driven by Saudis and Iranians. No, my joke is that in sort of where I live in suburban D.C., you can have a luxury car as long as it’s hostile to U.S. foreign policy. And they get picked up by these creatures I wrote about in one of my books called uber-moms who are highly successful career women who have taken time off to make sure their kids can get into Yale. And you can tell they’re uber-moms because they actually weigh less than their own children. At the moment of conception, they’re doing little butt exercises so they’re fit and trim. At the moment of delivery, they’re cutting the umbilical cord, flashing little mandarin flashcards at the things. By the time they reach me, they’re super achievement machines. I asked my kids, you know, “What their doing at spring break?” They’re like, “You know, I’m unicycling across Thailand while reading to lepers.” That sort of thing.

I love Yale, I love Yale and I love my students. But they’re a little imbalanced. The achievemenithosis is so strong, they really have little time for anything else. One of my kids said their spiritual side is undernourished. And one of my kids said, “We’re so hungry, we’re so hungry.” And they are hungry for that. And the thing I’ve seen in a couple of my kids (it’s always like 20%) is that their parents love them. Their parents are always so anxious for them to succeed. These two factors combined to the beam of love hits them very intrusively. But the beam of love is a little brighter when they’re doing what their parents want, what they think will lead to success. And then when they get off the balance beam, the beam of love diminishes and it gets bad. I’ve had some of my kids that took jobs their parents didn’t want and their parents not going to come to commencement. It becomes the wolf of conditional love sitting out there and when you see the parents withdrawing because the kid’s doing what they don’t want. You see the effect of conditional love, which is to undermine all the criteria that children or the students have. They’re so terrified of losing that love, the core love relationship of their life that it just dissolves them inside. And I’ve become fervent on this subject because the need for unconditional love and letting the kids make their own decisions… you know, those of us who have kids at this age, we did what we can do. And we can guide and we can advise. But to withdraw love based on the decision they can make on their own lives. It’s made me so militant on this subject. And I tell you kids, you owe your parents respect and you owe them honor and you owe them love… you don’t owe them your lives. And this is something I’ve seen the bad effects of this.

But Pitzer’s different. The atmosphere’s different. And Pitzer has the balance better. Schools that leave a mark, they have it in the classroom… but then they have a culture that you feel when you go in. And Pitzer has a nice balance. And that’s one of the things that I’ve valued in Naomi’s time here. And the way I think of this balance is that you can divide the virtues into two sorts of virtues: the resume virtues and the eulogy virtues. The resume virtues are the thing you bring into the marketplace. And the eulogy virtues are the things they say about you after you’re dead. Whether you were honest or courageous or brave. Whether you were capable of love. We live in a culture where we all know the eulogy virtues are more important but we live in a culture that praises the resume virtues and organizes and emphasizes the resume virtues. We’re just more articulate about those things. And most of us, including myself have spent most of our lives thinking about our career rather than how do I develop that that I’d like to have.

A book that helped my organize my thinking of this was a book written in 1965 by a guy named Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik called Lonely Man of Faith. And he says we have two sides to our nature, which correspond to these two virtues, which he calls Adam One and Adam Two. Adam One is the external resume Adam. It’s the one who wants to build things, create things, write books, discover scientific discoveries… make an impact on the world! Adam Two is the inner Adam, the humble Adam, who wants to be enveloped by love, security, and meaning. Not only to do good but to be good inside. To have inner soul that honors our own possibilities. So, Adam One wants to conquer the world, Adam Two wants to hear a calling and serve the world. Adam One savors accomplishments and Adam Two savors the scent of a warm meal, the atmosphere of people out for drinks. Adam One asks how things work. Adam Two asks why things exist and what ultimately we’re here for. Adam One wants to venture forth. Adam Two wants to return to roots. Adam One’s motto is success. Adam Two’s motto is love, redemption, and return.

Now Soloveitchik’s argument is that these two sides of our nature are in us and they’re both legitimate and they have to be balanced but they live in confrontation with each other: there’s tension between these two sides of our nature. And I bet that the hard part of this confrontation is that they live by different logics. Adam One, the external Adam, lives by an economic logic: input leads to output, practice makes perfect, and effort leads to reward. Adam Two lives by an inverse logic, which is a moral logic and not an economic one. You have to give to receive, you have to surrender to something outside yourself to gain strength within yourself, you have to conquer desire to get what you crave, and success leads to the greatest failure, which is pride. Failure leads to the greatest success, which is humility and learning. In order to fulfill yourself you have to forget yourself, in order to find yourself you have to lose yourself. We live in a culture that is so achievement-oriented, that that moral logic just drains away. It drains away at a lot of colleges.

There’s a sociologist at Notre Dame named Christian Smith who went around to college campuses, asking college students about their moral lives. He wrote a book called Lost in Transition. The main feature of the book is that they’re not bad. College students are amazing. But they’re inarticulate. They have no been giving categories to think about this stuff. So he asked, “Could you name your last moral dilemma?” And 70% could not name a moral dilemma. So they say, “I pulled into a parking space and didn’t have enough quarters.” It’s a problem; it’s not really a moral dilemma. They just lost the vocabulary. I think a lot of what colleges need to do is provide the academic research but provide the education at least to give them the vocabulary so as they go through life and bad stuff happens, they will know the vocabulary of morality and virtue.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this problem: we use all these words, what do they mean? They’re sort of fuzzy in our heads. So for example, we use the word character. Or we use death. We want to be deep. So what does that mean? What does it mean to have character? So I was thinking, what does it mean by that word when we use it? The first thing we mean is consistency over time. The things that lead us astray such as lost fear, vanity, and gluttons. The things we call character are long-term. Courage, honesty, and humility. The ability to have a long obedience in the same direction. Second, to have scope: not to be a free-floating person but to be firmly attached to things. In the realm of intellect, the person of character who has a set of permanent conviction about permanent truths. In the realm of emotion, a realm of unconditional loves. In the realm of actions, a permanent commitment to tasks that can’t be completed in a single lifetime. So scope. And then I think a third thing we’d say in someone of character is that they have some solidity inside. There’s a core piece of us. The part of us that makes moral decisions. And that core piece is fully malleable by us. If you make discipline choices, and you do things in a consistent way, you build that core piece into something solid and dependable. If you make selfish and shortsighted choices, you degrade that core piece, and you make it in constant fragments and your life will somehow fall apart eventually. Someone with character is trustworthy.

And we come to the liberal arts and what can we do to teach character? I once wrote a column about the difficulty of teaching it in the classroom. And I got an email from a veterinarian in Oregon, a guy named Dave Jal, who you’ve never met. He wrote, “The heart cannot be taught in a classroom intellectually to students mechanically taking notes. Good, wise hearts are obtained through lifetimes of diligent effort to dig deeply in and heal lifetimes of scars. You can’t teach it or email it or tweet it. It has to be discovered in the depths of one’s own heart. When a person is finally ready to go looking for it and not before. The job of the wise person is to swallow the frustration and just go on setting an example of caring and digging and diligence in their own lives.”

Then a couple sentences that really leapt out at me, “What a wise person teaches is smallest part of what they give. The totality of their life, of the way they go about it in the smallest detail is what gets transmitted. Never forget that the message is the person, perfected over lifetimes of effort that was set in motion of yet another wise person, now hidden from the recipient in the dim mist of time. Life is much bigger than we think. Cause and effect intertwined in a vast moral structure that keeps pushing us to do better, become better, even when we dwell in the most painful and confused darkness.” The senses that leapt out at me from this is that the job of the wise person or what a wise person teaches is the smallest part of what they give. The message is the person. I think that’s true of the teachers here and teachers of good liberal arts schools is that the way they become scholars and the way they approach ideas and they way they teach their students is what gets transmitted. I suspect if we all think back of the great teachers in our lives, it’s not the curriculum they taught, it’s who they were: their way of being. And I don’t think that’s totally it. It’s not just the example of the person, there’s something morally virtuous of understanding the world. And there’s something virtuous in having different vocabularies of morality from which to choose. And then there’s that we understand that people get better in their lives when they look at exemplars, when they look at people who came before, who have lived well. We can learn from them, at least how they did if we don’t know how we did. So if we go back and have a liberal arts education, which is filled with biography and filled with novels and filled with the arts, which widen the repertoire of our emotions, I do think we learn valuable things, not just the quality of the personality or quality of the culture of the place. And I’m sure if we all took college tours at the beginning of this process and if you go from college to college, the culture is so different in each place. They take individual kids from what might be demographically the same, and four years later the kids are just so different. They’re marked by the different culture, the power of each individual campus culture. But when I look at the people who I admire and I have read books about, there are certain activities that I do think lead to character and death.

I’ll list three or four of those activities that I think you’ve learned from biography novels. The first activity, we wouldn’t say someone’s character is in-depth if they were not capable of love. A book I read that exemplified this sort of love was written by a guy named Douglas Hofstadter, who’s a mathematician at Indiana Universality. And Hofstadter was married to Carol. And they had two children who at that time were five and two, when they went on sabbatical I think to Italy and Carol suffered an aneurism and died. Hofstadter had a picture of Carol on the nightstand. He looked at that picture every day probably after her death. Here’s what he wrote, “I looked at her face and I look so deeply that I felt I was behind her eyes. And all at once, I found myself saying while the tears flowed, ‘That’s me. That’s me.’ And those simple words brought back many thoughts that I had had before, about the fusion of our souls into one higher-level entity, about the fact that at the core of both our souls lay our identical hopes and dreams for our children, about the notion that those hopes were not separate or distinct hopes, but were just one hope, one clear thing that defined us both, that welded us into a unit – the kind of unit I had but dimly imagined before being married and having children. I realized that, though Carol had died, that core piece of her had not died at all, but had lived on very determinedly in my brain.“

He’s talking about a love that merges two minds together and so the first thing love does is humbles you. It reminds you you’re not in control of your own passions… we’re emphasizing on Valentine’s Day. It’s like an invading army you want to be invaded by. The second thing love does is it decenters the self. Egotism is desperate longing in a small space but the person love realizes the center of his life is not inside himself, it’s in another person. Montaigne said this, “Love eliminates the distinction between giving and receiving.” Because your lover is part of yourself so when you give to your live, you’re giving to yourself. Montaigne writes a friend who allows his friend to give him a gift is doing the greatest favor of giving his friend the pleasure of giving the gift. It decenters the self. The third thing love does is it opens up hard ground. It’s like a plow that digs through the crust and opens up the heart for something soft for a greater vulnerability. We all know people have been softened by love. And finally, love leads to service. One of my heroes is a woman named Dorothy Day. She read novels and she couldn’t just read novels, she became the novels. This young woman, she read a lot of Dostoevsky and so she drank a lot. She lived in the attic, she was really poor, she caroused a lot, she was depressed a lot… Suicide attempts, a couple abortions… Her life was somewhat of a mess. She had a child with a common law husband and she realized that all the accounts of childbirth she read were written by a man. So she wrote one. One of the passages said she wrote it like 40 minutes after giving birth. She said, “If I painted the greatest painting, sculpted the greatest sculpture, composed the greatest symphony, I could not have felt the more exalted creator than I did when I did when they placed the child in my arms. And with that came a need to worship and to adore.” That need to worship translated into faith, the Catholic Faith. She founded the Catholic Social Worker movement. She founded a radical newspaper, homeless shelters, and lived for 60 years. A life of unbelievable service, transformed by the love of her child and the gratitude that produced. What we see in love is that it humbles you, it decenters you, and then it lifts you up. And that would be the one thing all people of character have.

The second thing is suffering. People who have great character usually have a season of suffering. There’s Lincoln with depression, FDR with polio… and suffering is the same basic shape. First it humbles you. The theologian Paul Tillich said it “Drags you into deeper into yourself and reminds you you’re not who you thought you were.” Tillich wrote that suffering is like you have a hole: a floor in what you think is the basement of your soul. It digs through the hole revealing a cavity below and a cavity below and a cavity below. It just digs you into yourself. So suffering, like love, shatters the illusion of self-mastery. It digs you down but then pulls you up. It gives people a sense of calling. People have an instinctive sense to turn suffering into transcendence. I have a couple of friends who had lost a kid when he was six. They didn’t say, “Well we’ve been in grief for two years since the loss of Henry. So let’s go party it up to balance our happiness accounts.” Nobody does that. They wanted to connect their suffering and Henry’s suffering to something holy and transcendent. They created a foundation called Hope for Henry so other kids can be prevented from going through what he went through. They turned suffering from bringing you down to pulling you up. It’s that same V shape.

The third thing I’d say most people who have character have is a sense of calling and vocation. Another of my heroes is a woman named Francis Perkins who was the first cabinet secretary and the first woman in the cabinet under FDR. She was the first labor secretary. She was a highborn lady who went to Mount Holyoke in class of 1902. Holyoke was one of those colleges that left a mark on a student. The rules at Holyoke were a little different than the rules at Pitzer. One of the rules was that freshmen should not speak to sophomores. A freshman greeting to a sophomore on the sidewalk should bow respectfully. I don’t think that would work here. But it taught women in those times an incredible sense of heroic service. It sent them off around the world to do missionary work and to a work. There were single women in 1902 who were going off to Tibet, to Pakistan, to Africa, to the Middle East, all by themselves. Somebody did a census of American female missionaries abroad in 1920 and 30% of them were Holyoke grads. It was just an amazing place. She went there and was transformed by a heroic sense of service, which was focused until she was having coffee or tea in Washington Square Park in New York City. She hears a commotion, the ladies she’s having tea with rush outside, run across the square, half a block down, and they see a fire and they’ve stumbled across the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. From the 8th, 9th, and 10th floor of this building, they see what they think are bundles of clothing being thrown out the windows, but it’s like 9/11 with people jumping out the windows so they won’t be burned to death. She watches 57 people go over. One guy lifting a woman the woman over the window and dropping her into the space. And a second, and a third, and a fourth. His girlfriend, they kiss. He drops her and he goes over. At that moment, she hardened her vocation. She became dedicated to the cause of worker safety. She went up to Albany, became a lobbyist, discovered that the Tammany Hall legislatures were not taking her seriously. She realized she kept the folder at home called, “Notes on the male mind.” She realized that they would not take her seriously as a young woman, but she realized all guys would want to be loved by their mothers. So she dressed up as their mothers, like an 80 year-old woman with a frumpy woman with a frumpy dress, grey pearls, a hat. They nicknamed her Momma Perkins. She was a very successful lobbyist.

She found commencement speakers generally give college graduates incredibly crappy advice. Not only do we leave them all this debt, we give them bad advice, they’ll never pay it off. One of them is “find your passion/follow your passion.” You’re 22 and you’re supposed to look inside and find your passion. What Perkins did wasn’t think, “Well, what do I want from life?” She asked, “What is life questioning me to do? What are my circumstances questioning me to do?” And it was this fire that defined her life. Her health defined her life. The vocation came from outside. “What does life want from me?” Not, “It’s all about me, what do I want from the world?” She had a life of amazing service as FDR’s cabinet secretary. So I’ve described a couple things that I think lead to character. The love, the suffering, the vocation. They drag you out of yourself and then they lift you up. So there’s that same V-shaped pattern. Kierkegaard has a phrase, “The hero has to go to the underworld to rescue the beloved.” You have to go down to go up. So I do think that’s a pattern you see again and again in life. People who are able to defeat themselves. People who are aware of their deepest weaknesses and then make those weaknesses their strengths. That’s one of the things we see over and over and over again.

The final stage is at the end of it is grace. Grace is, of course, a religious word that means unmerited love. For the religious and the nonreligious, it means being held up by a people you didn’t expect. The people who go down and then come up find the hands that come to hold them. When you talk about character, it has this negative orientation that you have to develop character thorough character and self-discipline. That’s part of it. But the people you see who have real character and have real depth, they know that they are broken and sinful but they know that they require redemptive assistance from outside. You see them and they have a sense of humility. Sometimes you think humility is thinking lowly of yourself. It’s more accurately defined as not thinking of yourself at all or realizing that you’re unfit for the tasks that have been assigned to you or realizing you’re an underdog against your own weaknesses. My favorite definition is “accurate self-understanding from a distance.” The people we have that have these abilities. They have been held up by faith and they have committed themselves by something longer than their self-interests. If you look at Francis Perkins. If you look at Dorothy Day.

If you look at other heroes of mine, George Marshall, who’s life was dedicated to military. If you look at Bayard Rustin and Phillip Randolph, underrepresented civil rights heroes. They have all gone through this period of brokenness and they have all come out. What we see at the end of their lives, is a moment of tranquility. This is sort of the reward. It’s not chased, but it’s the by-product of people who have gone through this process. I mentioned Day, let me mention another figure who Day modeled her life around, Saint Augustine. Augustine had over pressuring parents. He had the helicopter mom to be all helicopter moms. Her name was Monica, he was like 27, he had a kid. He wanted to leave Africa and Monica wouldn’t let him. He had to trick her, get on a boat, she’s on the shore screaming at him. She chases him across to Italy. She spends her life hounding him. She makes him divorce the woman he loves so he could marry a 10 year old. She’s completely pressuring but completely loving. He can’t get away from her. He loves her and he hates her. At the end of his life, he has his famous scene in a garden where he becomes a Christian. Monica says to him, “I wanted my life for you to become a Christian of this sort and you have. God has given me this. “ It becomes clear as they’re talking that this is it for her. She’s had what she wants from life and she’s ready to die. In fact, she would die nine days later. As Augustine records the conversation, they’re sitting in a different conversation and they’re talking. He talks about the sweetness of the conversation after a lifetime of conflict. He has a long sentence of how they’re merging. After a difficult relationship, they’re becoming one. He has a long sentence, which is very hard to read and understand – it’s very long and very complicated – but there’s a word in it that appears again and again and again, and that word is hushed. The sound of the breeze was hushed. The sound of the birds was hushed. The sound of the wind was hushed. The sound of our voices was hushed. The sound of our hearts was hushed. The sound of our cells was hushed. Even the sound of hearts was hushed. You get this great sense of this tempestuous settling into peacefulness and gratitude. It’s when you see people have achieved great character (and they may not be famous)… I’ve met some women who teach immigrants to read and it takes them seven years to teach them the language and how to read. Incredible patients and they have that settled steadiness of voice that I associate with Augustine. That’s the by-product of not needing to strive anymore when Adam One bows down to Adam Two. As Brian Williams learns, Adam One, there’s no satisfying. But Adam Two can be satisfied. His needs are not limitless. I think when you have a liberal arts education and you go to a college like this one, you converse with those sorts of lives and you become conversant with those writers who know you better than you know yourself, who can teach you about yourself.

One of those writers for me was a guy named Reinhold Niebuhr, a theologian from the 50’s, every Jew’s favorite Christian. He had his sentence which sums up a lot of what I’ve been saying: “Nothing that is worth doing can be achieved in our lifetime; therefore, we must be saved by hope. Nothing which is true or beautiful or good makes complete sense in any immediate context of history; therefore, we must be saved by faith. Nothing we do, however virtuous, could be accomplished alone; therefore, we must be saved by love. No virtuous act is quite as virtuous from the standpoint of our friend or foe as it is from our own standpoint; therefore, we must be saved by the final form of love, which is forgiveness.” I do think that’s the sort of paste moral wisdom that is at the end of, first, the liberal arts education, and then the life that’s lived into the seeds that were planted when you were 18 to 22. Thanks. [Applause]